You probably didn’t understand Anora.

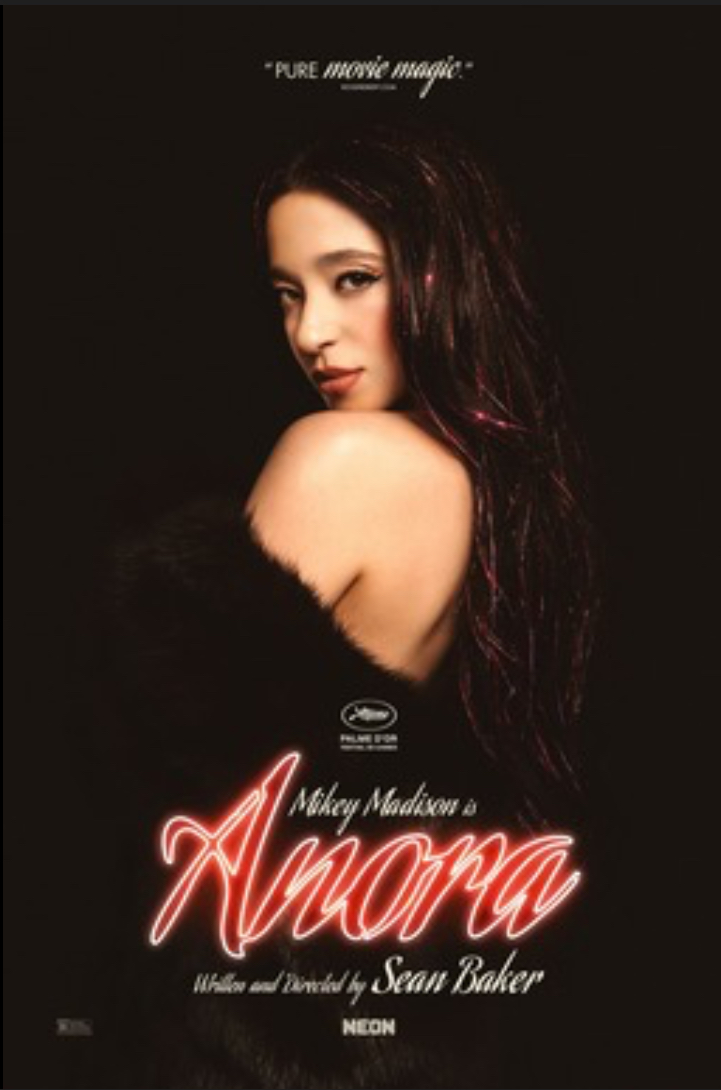

The acclaimed 2024 film has gotten both hate and misunderstanding for winning “Best Picture” at the Academy Awards. “How could a raunchy movie about a stripper be dubbed the best film of the year?” People exclaimed in surprise.

Well I’ll tell you!

The 2024 film isn’t just about a stripper who marries the son of a Russian oligarch—it’s about the way that capitalism turns everything, from love to labor, into a transaction.

At first glance, the story feels almost like a fairytale: Ani (played by Mikey Madison), works at a Brooklyn strip club, where she meets Ivan, a rich Russian heir. A whirlwind romance later, and they’re in Las Vegas, exchanging vows, rings on fingers. But what follows isn’t a happily ever after—it’s a brutal negotiation of power, money, and personal autonomy. One that exposes the underbelly of economic inequality in ways that most films would be too afraid to cover.

Ani is a stripper. Not a princess locked in a tower waiting to be saved, not a tragic figure suffering through her work, but a professional, fighting tooth and nail to make a living. Sean Baker, the director, has spent his entire career portraying the lives of people whose work is often stigmatized—like the porn stars in Red Rocket, sex workers in The Florida Project, and now Ani, a woman who understands that stripping isn’t about seduction, it’s about survival.

Capitalism is the hidden antagonist of the film, and defines Ani’s choices at every turn. The strip club where she works is one of the few spaces where she can exert control over her own labor, where she can set the terms of the engagement. But outside of that world, she’s constantly at the mercy of people with more power and more money.

In Anora, itself is another financial arrangement. Ani and Ivan may like each other, may even love each other in their own impulsive way, but their marriage is quickly reduced to a constant battle between her and his family. The oligarchs don’t see marriage as romance:, they see it as an economic merger, a potential liability if not done “correctly.”. They see Ani not as a human being, but as a pawn, and when they realize they have no “use” for her, they attempt to buy her out of the relationship, treating her like an inconvenient business investment.

Baker doesn’t do this for melodramatic effect—he does it to showcase brutal realism. What is marriage under capitalism if not a financial agreement with emotional side effects? And what does it mean for someone like Ani, who has spent her entire life working for every single dollar, to suddenly be surrounded by people who make money effortlessly?

Ani’s brief brush with wealth isn’t about luxury—it’s about control. She sees firsthand what money does. It protects, it manipulates, it easily erases consequences. The top 1 percent live in a world without accountability, while everyone else scrambles to simply stay afloat.

There are no easy answers in Anora, and that’s exactly the point. Baker isn’t interested in telling another Cinderella story. Ani is both victim and perpetrator, trapped and free, playing the game as she fights against it.